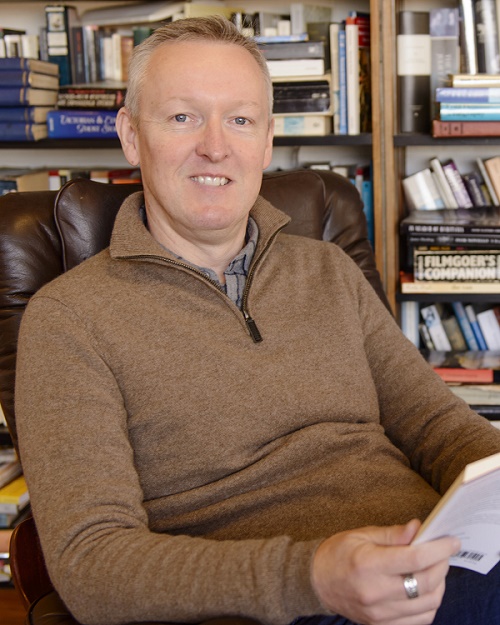

Nicholas Daly is Professor of Modern English and American Literature at University College Dublin, and a member of the Royal Irish Academy. His publications include the books Modernism, Romance, and the Fin de Siècle (1999), Literature, Technology and Modernity (2004), Sensation and Modernity in the 1860s (2009), and The Demographic Imagination and the Nineteenth-Century City: Paris, London, New York (2015). He recently edited Baroness Orczy’s The Scarlet Pimpernel for Oxford World’s Classics, and he is currently completing a project on Ruritanian fiction, drama and film, from The Prisoner of Zenda to The Princess Diaries.

In which directions do you think nineteenth-century scholarship should evolve in the near future? Most of the things that I would want are already happening: for instance, the turn towards transatlantic and global perspectives; the interest in affect, ecology, and animal studies. I suppose I would like to see more work on the theatre, since it rarely receives anything like the level of attention of the novel. But I believe nineteenth-century studies is in pretty safe hands: I see a younger generation of scholars doing exciting and original work, despite the continuing precariousness of the academic job market.

What is your favorite nineteenth-century quotation? The opening paragraph of Bleak House is probably my favorite piece of Victorian prose. But if I can choose a shorter and less familiar piece that gives a very different version of the nineteenth-century city, it would be a line in a comic music-hall song by Frank Hall that has always amused me. The song is The Properest Thing To Do (1863), and it features a married would-be man about town who gets into comic scrapes when he heads out on a spree. Early on the protagonist confidentially tells us that “Mr Fitzplantagenet: that’s my name when I go out.” It is just a throwaway detail, but it suggests in parvo a whole world of cross-class dressing scoundrels, chancers, and ne’er-do-wells who walk the streets of the Victorian city not as a place of mystery and melodrama, but as a resort of pleasure and self-invention. This song offers a male fantasy of the romance of city life, but the female characters who appear in similar songs are just as much on the make. Such popular pieces seem to me to offer a valuable corrective to our usual take on mid-Victorian life, which leans heavily on the writings of the respectable middle classes. In this regard, I really admire Peter Bailey’s work on music hall and on the invention of modern “fun.”

Which country / decade of the nineteenth century would you like to live in if you could go back in time? I work on Victorian Britain, and part of me would love to see Victorian London. I am not at all sure, however, that I would want to live there, given the high mortality rates, the gaping chasm between rich and poor, and quotidian urban squalor; some of the factors that lend vitality to Victorian writing would make for challenging living conditions. If I could go for a very short visit, it would be to the first day of public admission to the Great Exhibition of 1851. We have a rich array of sources to help us to imagine it, but I would love to see it for myself, and to see how people reacted to the “Crystal Palace” and its staggering array of things. With hindsight we can see that it points towards the consumer culture of the future and the unsustainable ransacking of the world to sate metropolitan appetites, but I would still like to encounter it as it seemed to its first visitors.

If you could go back to the nineteenth century to change one thing, what would it be? I don’t often get a chance to change history, so I may as well aim high. I’m Irish, and as readers will recall the Irish experience of the nineteenth century was dominated by one apocalyptic event, the Great Famine (1845-1852), which killed more than a million, and drove an even greater number to emigrate, when the total population of the country was around 8 million. (Poorer communities were heavily dependent on a single crop, the potato, and when disease destroyed the crop in successive years the effects were devastating.) The disaster was exacerbated by the attitudes of Ireland’s British rulers, some of whom felt, like contemporary neoliberals, that the market was the answer to everything, and that official aid was an unwarranted interference. The Famine’s long-term effects on Irish society were so deep and wide that it is hard to imagine now what the country would have been like if it had never happened, or even if its worst effects could have been mitigated. So that is the thing I would change.

Is there anything from the nineteenth century you wished would come back into fashion? I’m not sure about fashion, but if we are bringing things back: the quagga, the passenger pigeon, the Atlas bear…

Published by